Do you have to know someone to be successful as an entrepreneur? The answer is Yes. But who you need to know may surprise you.

When Dr. Saras Sarasvathy was doing research on entrepreneurship, she had a hunch that successful entrepreneurship didn’t originate from a business plan or market research. She herself had started new ventures and surrounded herself with other successful entrepreneurs who were able to start or grow new businesses without sophisticated forecasting and modeling tools.

So if they didn’t use planning, what did they use? For this answer, Dr. Sarasvathy sought out the most successful entrepreneurs she could find and put them through a start up problem solving scenario that she recorded. She interviewed entrepreneurs who started multiple ventures with successes and failures and they all had at least one IPO. At the conclusion of the interviews she looked for behaviors common to all of these entrepreneurs.

What she found was that all of them knew someone who helped them get their venture off the ground. Yet not all of these entrepreneurs had:

- An Ivy League education;

- A parent who worked in venture capital;

- An MBA;

- A family member in a CEO role; or

- The support of a high ranking political official.

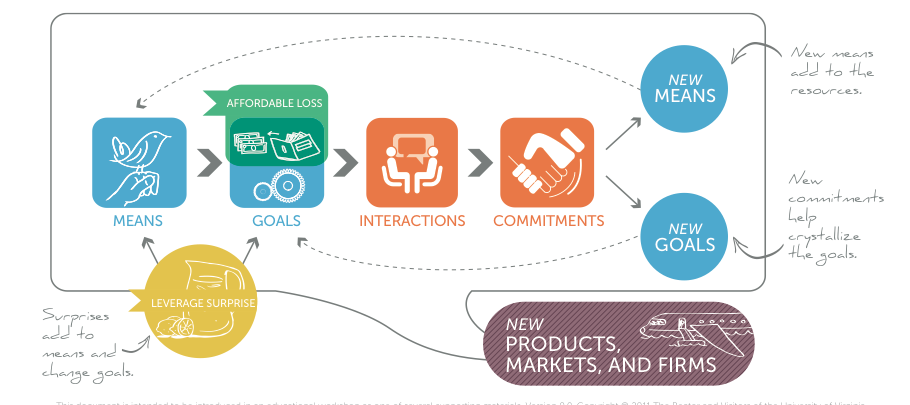

If money, power, or influence wasn’t a commonality among these entrepreneurs, what was? Who was it that played a significant role in getting their ideas to market? The commonality is that there was no one person in one specific role who made it all happen. Rather, it was the process of being open to engaging all types of individuals that made these entrepreneurs successful. Some of those contacted became co-founders and colleagues. Some became collaborators and advisors, who opened the door to other opportunities beyond those immediately apparent to the entrepreneur. Others became customers, partners, or suppliers.

The transcendent factor in all of these relationships was that each stakeholder opted to participate in the venture with the founding entrepreneur. And their participation was not just verbal. The stakeholder committed to bringing some of their assets to the endeavor in an effort to jointly grow it beyond its original state.

For those who think that entrepreneurship is all about who you know – they’re right. But it’s not about finding the perfect person to connect with - someone with the most money, power, or influence. It’s really about building a broader network. About engaging those you know – whoever they may be. Rank and role becomes secondary to commitment.

Entrepreneurs can act on these findings by engaging those in their family, personal and professional networks, and even those with whom they have chance encounters. Talk to people. Tell them your ideas. Share your goals. And if they express interest, ask for more than feedback – ask for commitments. It turns out that what you ask for – commitments – is even more important than who you ask.

--Written by Sara Whiffen, Founder & Managing Partner, Insights Ignited LLC